In Eyüpsultan—one of Istanbul’s spiritual heartlands—Murad al-Bukhari Lodge (also known as Shaykh Murad Efendi Lodge) has long been a place of learning, service, and quiet reflection. As an early centre of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi tradition in Anatolia, it preserves a legacy shaped by scholarship, community, and inner peace.

Established in the 17th century as a madrasa by the Anatolian chief military judge (Anadolu Kazaskeri) Çankırılı Mustafa Râsih Efendi, the site began as a setting for formal learning in Eyupsultan. This early educational identity shaped the character of the complex: study, discipline, and service. In time, the building’s function and community expanded beyond a school, laying the groundwork for what would become one of Istanbul’s notable Sufi lodges—rooted in both scholarship and spiritual refinement.

In 1681, Murad al-Bukhari—already trained in the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi path through his connection to Muhammad Ma'sūm (son of Imam Rabbani)—arrived in Istanbul and was welcomed by scholars and leading figures of the city. He settled in the Eyupsultan area (Nişancı), where his presence helped anchor the Mujaddidi tradition in Ottoman lands. His life story—marked by travel, teaching, and perseverance despite physical disability—became part of the Lodge’s moral memory and shaped the tone of its later gatherings: learning, humility, and inner renewal.

In 1715, the madrasa was converted into a lodge (tekke) and dedicated to Murad al-Bukhari by Şeyhülislâm Damadzâde Ahmed Efendi (son of the original founder). With this transformation, the site became a major spiritual and educational centre: a place where guidance (irshad) and learning could be carried together. Accounts emphasize the Lodge’s scholarly emphasis—its library culture and the teaching of major hadith sources, including readings of Sahih al-Bukhari—alongside a community life shaped by remembrance, discipline, and hospitality.

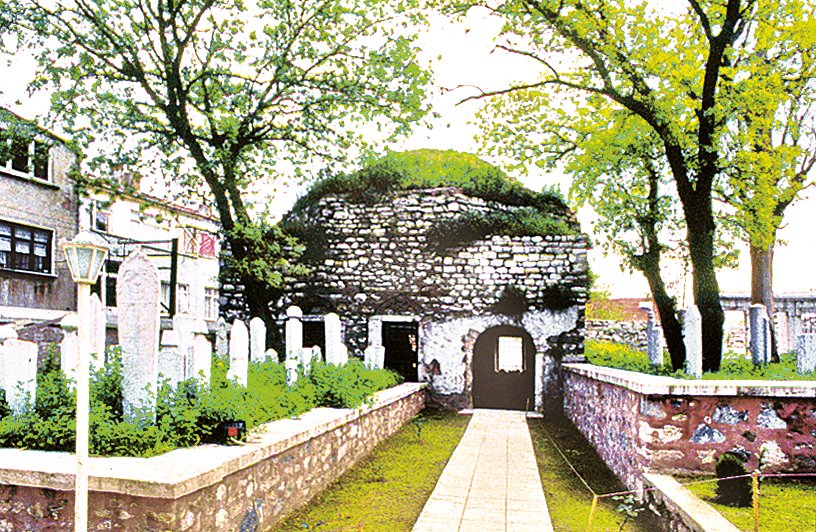

Murad al-Bukhari passed away in 1132/1720 and was buried within the complex, in the space used as mescid–dershane / mescid–tevhidhane. With his burial, this part of the building also took on the character of a türbe, turning the Lodge into both a living institution and a place of visitation. The lodge’s continuity was maintained through subsequent shaykhs; sources note that the second shaykh, Kilisli Ali Efendi, was also later buried there. In this way, the site developed a layered identity: prayer, teaching, remembrance—and a lineage that shaped the Lodge’s spiritual atmosphere over generations.

During the 18th century the Lodge grew into a fuller complex (külliye) through additions and upgrades. Records note a fountain and shadirvan commissioned for the tekke (with dates given in the 1730s tradition), and later the placement of a minbar in the mescid–tevhidhane, reflecting the evolving public and communal function of the prayer space. In the same period, the programme expanded with facilities that supported daily life—such as spaces for hospitality and service—and the complex gained architectural layers that expressed its maturity as a sustained institution rather than a single building.

A major turning point came in 1272/1855–56. Sources describe the earlier prayer hall’s deterioration and the creation of a new mescid building with a more practical plan, positioned to serve the community and lodge gatherings. In the same period, the selâmlık and harem sections were renewed, reflecting a broader rehabilitation of lodge life and infrastructure. This phase effectively rebalanced the complex: preserving the older tomb-linked core while providing a renewed congregational space suitable for regular use. Architectural inscriptions and dated panels from this period also reinforced the sense of continuity—renewal without rupture.

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, archival documents indicate multiple rounds of repair and maintenance carried out under the Evkaf administration (noted for 1897, 1898, and 1907). These interventions are important because they show the Lodge was not an abandoned relic at the time: it remained institutionally recognized and physically cared for. In the life of historic complexes, such cycles of repair are often what protect a site from irreversible loss—ensuring roofs, walls, and key functional spaces survive into later generations.

Following the closure of lodges in 1925, the complex was left to decline. Later urban pressures—especially after the 1950s—accelerated damage and loss: several auxiliary structures (including elements such as the shadirvan, fountain, hamam, and the harem/selâmlık) disappeared, while remaining buildings suffered heavy deterioration. In the 1980s, restoration was initiated by the General Directorate of Foundations (Vakıflar Genel Müdürlüğü) and later completed through civil stewardship, enabling the site to be used again for cultural purposes.